Retrofitting social housing: a new mixed funding model

Summary

At the heart of the problem is the simple fact that the energy cost savings of a retrofit project are insufficient to cover the initial costs. Not only this, but any savings that are achieved go to the tenant of the property rather than the housing association landlord who pays for the retrofit.

This initial cost can be reduced in three ways:

- Economies of scale to reduce costs of labour and materials

- Grant funding to reduce housing association’s own cost

- Guaranteed debt funding to minimise cost of raising capital for retrofit

In addition, battery storage can maximise the benefit of PVs installed during the retrofit and secure the best possible cost savings by reducing the need to purchase electricity from the grid.

Together these four changes would allow a retrofit project to achieve a positive rate of return over a 30-40 year period, whether this was a shallow retrofit (D-C) or a deep one (D-A).

Whilst the benefit would still go to the tenant, an association would be able to choose to recuperate some of the benefit from tenants, whether through service charges or rent increases, without leaving the tenant net worse off over time.

The Route to Financial Viability

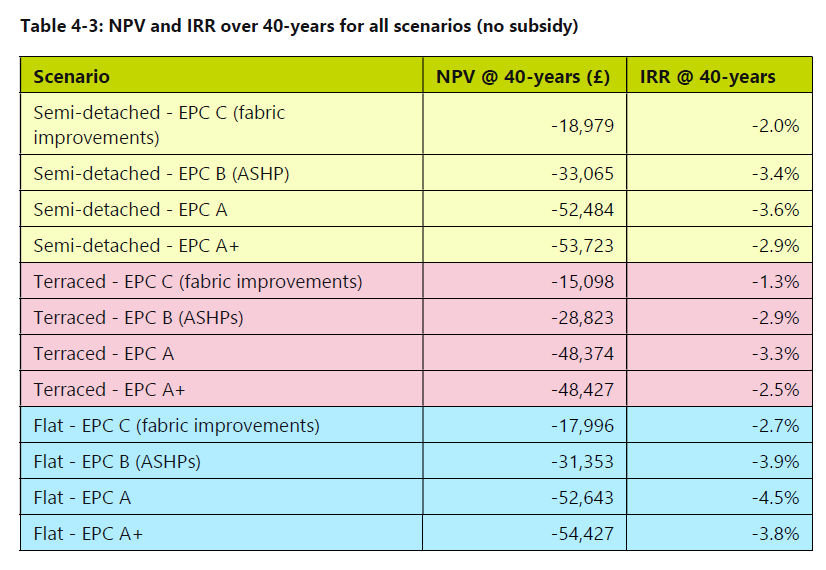

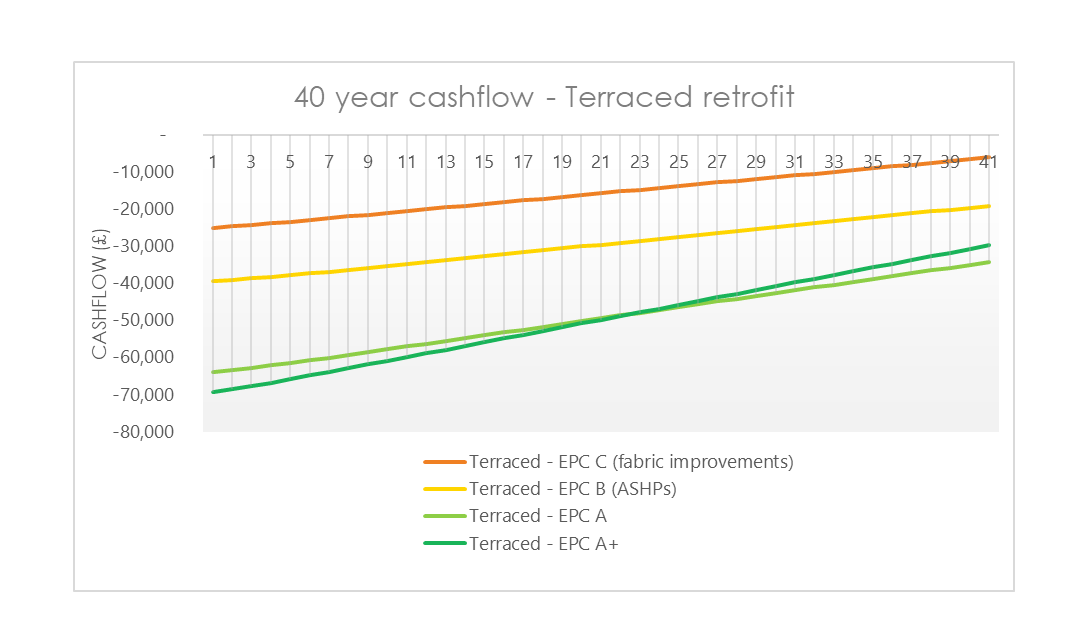

The cost savings achieved through energy savings are modest relative to the capital required. This makes any retrofit project loss making from the outset.

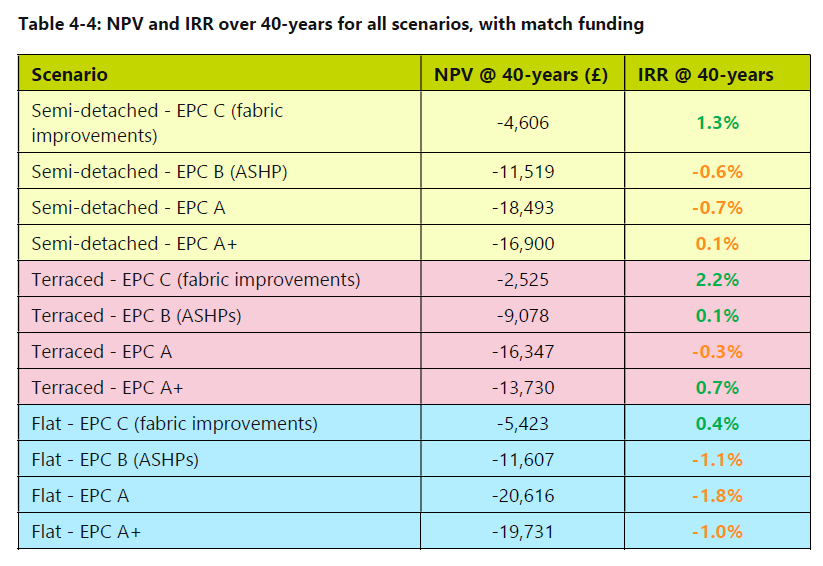

The effect of 50% grant funding is to make certain retrofit projects financially viable, mostly those improving an EPC D house to EPC C. This is because the capital cost of retrofitting D-C is c. £25k compared to almost £70k for EPC A+. Even here, though, the rates of return are under the 3% typical of a public sector type investment proposal.

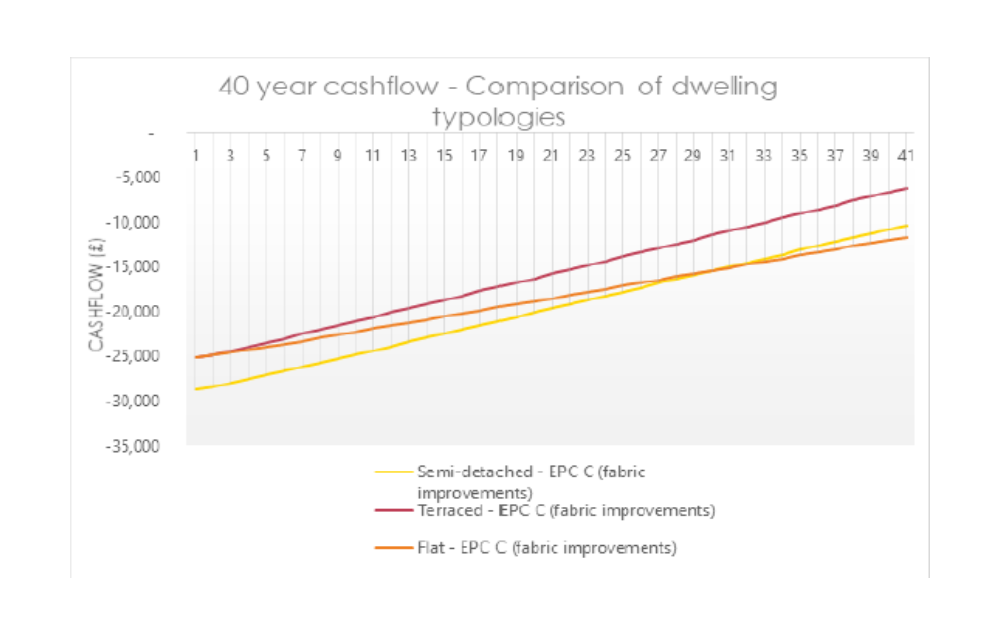

Across all three dwelling types modelled, the EPC fabric improvement retrofit achieves a return when allowing for match funding. For terraced houses the cashflow becomes positive after just 28 years.

Even with grant, then, many retrofit projects still remain loss-making over 40 years. The association is also still left to pay the other half of the capital cost, and to avoid widespread stock disposals to raise cash for this, it is likely debt funding will be required.

The way forward: combining grant funding with borrowing

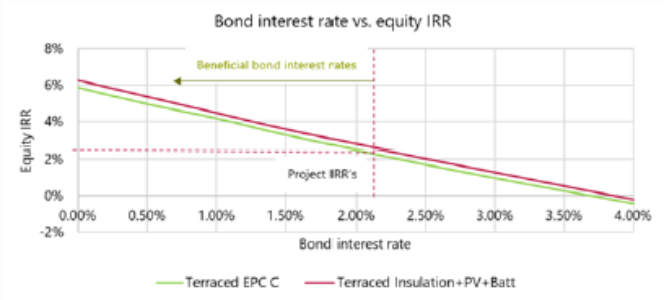

It is clear that a combination of both capital funding and low-cost borrowing would be required to generate positive financial scenarios.

The modelling shows that low rates and long bond terms provide the best conditions for a retrofit projects.

Over the last 18 months there have been several public bond issues by housing associations and aggregators that have achieved rates of around 2%. In September 2021 Stonewater HA issued a £350m sustainable bond at 1.625% with a 25 year maturity.

However, while part of the reason for the possibility of such rates is the low credit spreads in the social housing sector at the moment, the other part is historically low Gilt yields since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic in March 2020. It is unlikely that yields will remain so low over the next few years, and so it cannot be assumed that future issues will achieve comparable rates.

Government Guarantees are a key mechanism to ensure access to such low rates. Two schemes of this kind exist in the housing sector: Affordable Homes Guarantee Programme 2013-2016, Private Rented Sector Guarantee Programme 2013-2016. The former was run by Affordable Housing Finance Plc, a subsidiary of THFC, and saw £3.2bn issued at record low rates and on-lent to housing associations for the development of new affordable housing. The latter scheme was run by ARA Venn for the development of new private rental sector housing. The bonds issued under these schemes were subject to a Government Guarantee and as a result achieved much lower rates, close to the cost of Government borrowing. A second Affordable Homes Guarantee Programme was announced and awarded to ARA Venn in 2020, however loan proceeds can only be used by housing associations for the development of new housing, not for retrofit.

A new guarantee scheme for social housing retrofit would achieve significantly lower interest rates and therefore provide a reliable route for housing associations to access the debt funding needed to begin scaling up their retrofit programmes.

Economies of scale

The final part of the retrofit equation is to achieve economies of scale. At present there is not a industry capable of retrofitting on a scale big enough to achieve cost efficiencies. In part this is due to a lack of skills and knowledge, as well as the costs of still fairly new technologies. However, there is also a lack of demand caused by the hesitation around retrofit, largely because home owners and managers are generally waiting to see how the Government reacts and whether it will put in place funding or new legislation.

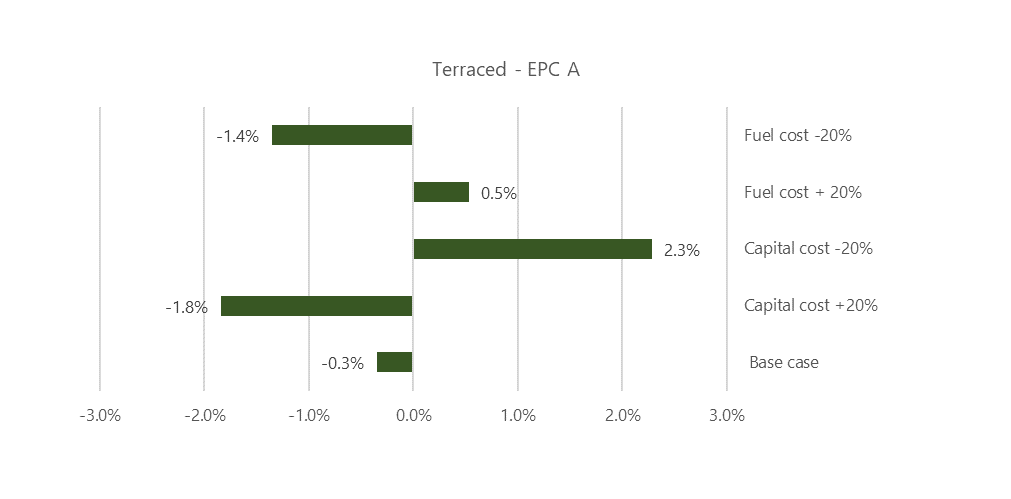

Economies of scale are vital if the cost of retrofit is to be brought down. As the cost savings won’t be affected, a reduction of capital cost will have a significant effect on the financial viability of retrofit. For example, the retrofit of a terraced house from EPC D to EPC A would achieve a rate of return on investment of just -0.3% over 40 years even with match funding. Were capital costs to be reduced by 20% this rate of return would suddenly increase to 2.3%.

If the required combination of grant funding and guaranteed debt funding put in place, this would provide a big incentive to housing associations to begin actually spending money on retrofit. The channelling of capital into retrofit would likely help to begin scaling up the industry and realising economies of scale.