As Safe as Houses: Are housing associations as good an investment opportunity as utilities?

2013-07-16

Key points:

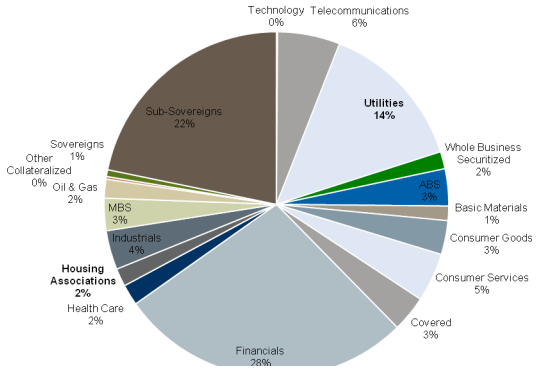

- UK housing associations share most of the attractive investment characteristics of regulated utilities and are generally rated more favourably than utilities by the credit rating agencies. Yet while the utilities make up around 14% of non-gilt Sterling debt currently held, housing associations account for just 2%.

- Part of this discrepancy is probably due to history. Utilities have a 20 year record of engagement with and significant borrowing from the institutional investment market; HAs have come to the market mainly in the last five years. Evolution of financing needs and models between the sectors has been very different. Consequently, understanding amongst investors of the relative business constructs is very different too. The largely charitable, not-for-profit nature of HA businesses takes time to get to grips with, compared to the more common and easily recognised plc model of most utility companies.

- Despite the differences in construct and ways of working between the sectors, from an investment perspective both benefit from strong economic regulation designed to ensure ongoing viability and protect the consumer interest. This includes inflation-linked annual price increases, recognition in some form of capital investment needs, and strong regulatory enforcement powers and intervention records to maintain organisational and sector stability. Both sectors have well established mechanisms for dealing with major viability issues and have seen potential failures averted by government or regulator action. Core regulated assets are protected, even where a transfer of assets is necessary.

- Analysis of the two sector models indicates that both continue to represent very low risk investment. Revenues from both are predictable, stable and inflationlinked from largely captive markets and neither sector is yet testing the limits of its ability to borrow.

- However, both sectors face considerable challenges over coming years which are likely to increase borrowing requirements. The utilities will need to deliver very substantial infrastructure investments, meet tougher efficiency and customer service targets and will see increasing competition. Housing association finances will come under some pressure from the government’s welfare reforms, continuing low development grants and growing competition. In both sectors, though, the challenges look financially manageable.

- The analysis suggests there is significant scope for housing associations to increase their share of the institutional investment market and investors may not yet be sufficiently aware of the opportunity the sector represents for safe but solid medium to long-term returns. Housing associations could support higher investment by engaging more consistently with investors (including international investors), and publishing more regular and transparent financial and service performance information. The housing association regulator is also reviewing the case for stronger ring-fencing of core assets and greater transparency of risks, including recovery planning. This could further support investor confidence in HAs.

Introduction

UK housing associations share most of the attractive investment characteristics of regulated utilities. But while the utilities make up around 14% of non-gilt Sterling debt currently held, housing associations comprise just 2% of the iBoxx index.

The question is whether this differential is justified by business fundamentals and technical factors or whether the investment market has not yet fully recognised the potential opportunity in housing associations.

England’s 1,500 regulated housing associations own around 2.6 million homes, more than half of the country’s social housing stock (with local authorities owning the remainder).

Similar to the utilities, housing associations:

- Have very strong asset bases with stable long-term revenue streams

- Operate in a highly regulated environment, backed by government

- Have price increases (rents) linked annually to inflation

- Don’t go bust. No housing association has ever been allowed to fail

- Have captive markets – demand far exceeds supply and there is little competitive pricing pressure

- Serve customers who have little or no alternative choice of supplier

- Operate within relatively ‘light touch’ consumer protection regulation

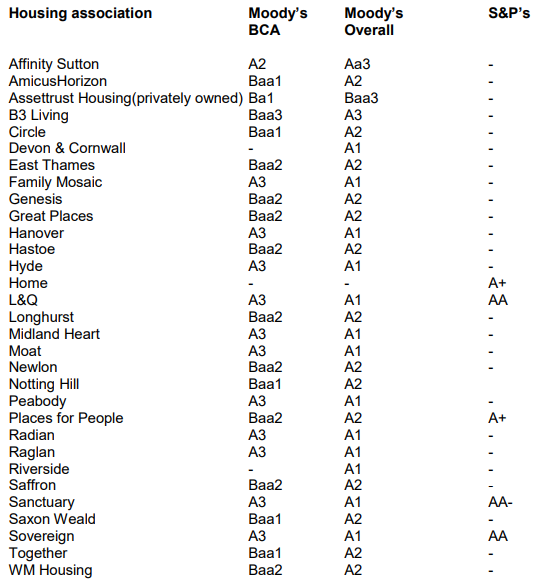

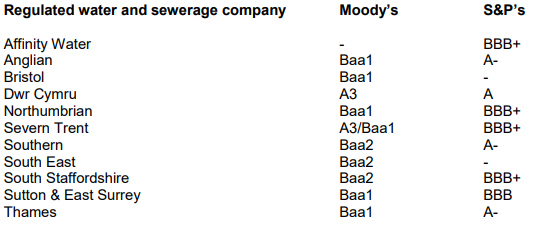

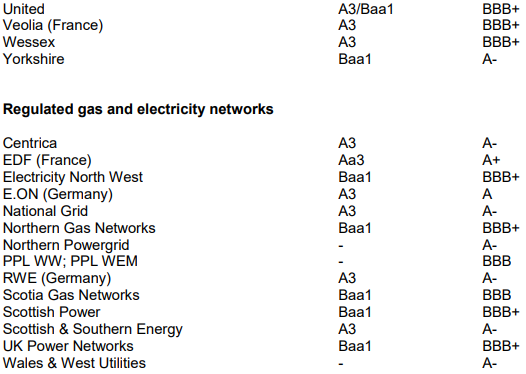

The credit rating agencies rate housing associations more favourably than the utilities. Even after a recent sector wide downgrade, Moody’s rates 30 rated associations mainly at A1 or A2, with one at Aa3 and one at A3. This compares to ratings for 14 water sector companies in the range of A3 to Baa2. The limited number of housing associations rated by Standard & Poor’s hold ratings of AA to A+, against S&P’s ratings of UK regulated utilities mainly at A to BBB (see appendix on pages 19 & 20 for full ratings list).

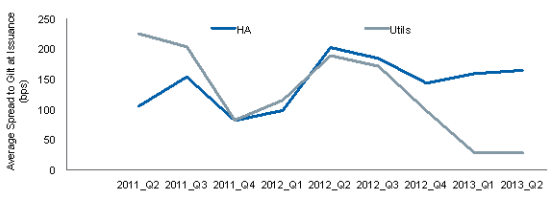

Despite these higher ratings, housing associations have tended to pay more for their debt than water and energy utilities (though the relative dearth of high quality bond issuance in recent months has seen comparative spreads between the two sectors compress)

Six month trailing average for six month spreads of housing associations compared to utilities

Is this a reflection of deep-seated and rigorous analysis of the two sectors by the investor market or are other factors also in play, perhaps connected with the relative lack of exposure to the market of housing associations and a consequent lack of real clarity within the institutional investor community about the business model and the

risks and opportunities investing might entail?

Certainly, some investors have started picking up on the strengths of the housing association sector and the prospects it may offer. In 2012/13, there were 16 own name housing association bond issues and the sector borrowed a significant £4.4 billion in the market, as investors spotted the relative value in HA paper. This was a huge increase on the £0.9 billion of the previous year, but still far below the £7.3 billion issued to utilities in 2012.

In total, since 1988 around 140 HAs have accessed the market either directly or indirectly through aggregating vehicles such as The Housing Finance Corporation. There is probably potential overall for around 200 of the larger housing associations to obtain bond finance, a size of market considerably in excess of utility numbers, albeit many of these housing associations will be smaller entities.

This paper compares and contrasts the two sectors, examining their relative strengths and weaknesses from an investment perspective and the potential future investment opportunities each offers. It considers why the variance of bond issuance between the sectors is so large and what more housing associations could do to present their case to the investor market to grow their market presence and share.

Evolution of the business and funding models

The very different manner in which utilities and housing associations have developed their businesses over the years is at least partly responsible for the variance in investor perception and knowledge between the two sectors.

Utility model

The privatisation of the water and energy utilities took place in a concerted burst in the late 1980s, through a series of Acts of Parliament including the Gas Act 1986, the Electricity Act 1989 and the Water Act 1989. At the same time as privatisation took place, economic regulators were established with the principal purpose of protecting the consumer interest by setting the pricing mechanism (with regular reviews), monitoring service levels, monitoring ongoing investment in infrastructure, and encouraging competition where this is seen to benefit consumers. In truth, the private companies act as monopolies (water) or near monopolies (energy) within their markets and genuine competitive pressure on consumer pricing has been weak.

As the infrastructure privatisations of the 1980s progressed, so the legislative and regulatory models were honed, with strong similarities between different utilities. Public debt was written off at privatisation and the new private limited companies started life with a clean slate, but heavy financing requirements to deliver the necessary upgrades to the infrastructures they had inherited. The need to invest in the asset base to meet regulatory requirements and maintain the value of the assets is ongoing.

Utilities have financed close to half of their borrowing since privatisation through the bond markets and the proportion of bond debt to bank debt is growing. The sector has found a ready market, attracted most obviously by the ‘safe haven’ nature of the investment, the strong income generation streams, and the clarity and comfort provided by the regular inflation, capital expenditure and debt requirement linked uprating of assets in the Regulated Asset Base (RAB) through five yearly pricing reviews by the regulator.

The ‘plc’ corporate structure of most of the utilities is understood and recognised. Non-executive directors and senior management teams are answerable to shareholders, providing an added incentive to deliver good financial returns and maintain strong corporate performance and plans.

The nature of the core business model is also simple and clear to investors and there is a hard regulatory ring-fence separating core business and assets from other nonregulated activities the utilities might undertake. While Standard & Poor’s do not consider the ring-fence provisions sufficient in themselves to prevent distress of a regulated subsidiary from parent company credit deterioration, most of the utilities have limited exposure to non-regulated activity. Only two water companies (South Staffordshire and Veolia) derive a significant part of consolidated revenues and profits (around 20%) from non-regulated business, for example.

Investors have basically concluded that the government, through the regulator, will always stand behind the core infrastructure assets if necessary because of the political consequences and national economic and social cost of not doing so. Financing utilities feels like a gold-plated investment.

The rise of housing associations

The evolution of housing associations has been very different. The sector developed out of the traditional almshouses movement, housing the poor, and the earliest housing associations were mostly created by wealthy philanthropists and social reformers. The pace of formation increased rapidly in the 1960s, particularly from 1966 when the screening of ‘Cathy Come Home’ powerfully illustrated the human cost of homelessness and poor housing conditions.

The core activity for housing associations remains to build, acquire and manage homes for social rent to people who cannot afford to buy or rent in the open housing market. Social rent levels have traditionally been subsidised by government with development grants and the provision of revenue support through Housing Benefit.

The establishment of the Housing Corporation as the government’s investment agency and regulator for HAs in 1974 enabled associations to access substantial government grants to build homes for the first time. Through the 1970s and much of the 1980s, however, housing associations remained relatively small players in a social housing world dominated by local authorities.

The ‘big bang’ for HAs came with the 1988 Housing Act, which formalised housing associations’ role as the main developers of new social housing and enabled them to borrow sizeable volumes of private finance for the first time. Local authorities were effectively cut out of the development picture entirely during the 1980s and by the 1990s were being encouraged by the government to transfer their housing stock either into new or existing housing associations, partly to support large scale investment into existing social homes without the cost impacting on public borrowing.

In the 25 years since the passing of the 1988 Act, the sector has grown exponentially, and so too have its private financing requirements. Housing associations currently hold £48 billion of private sector debt, with a further £44 billion of public grant investment on their balance sheets.

How financing needs have grown and been met

In 1988 housing associations received a government capital grant of 90% of the cost for every new social home built. Since then, the proportion of development finance provided by government has fallen incrementally. Under the last Labour government’s large National Affordable Housing Programme of 2008-11, which delivered 50,000-60,000 new affordable homes a year, housing associations were financing around 60% of the cost of each new home built.

The Coalition government has introduced further major changes to the social housing development regime, partly for policy reasons and partly within the context of its broader austerity measures. Under the Affordable Housing Programme for 2011-15, housing associations now only receive around 20% government grant for each home built and are expected to finance the remainder through internally generated subsidies and higher borrowing, supported by higher yielding ‘Affordable Rents’ priced at up to 80% of private market rent levels (compared to previous social rent levels averaging around 50-60% of market rates nationally and more like 30-40% in London). Effectively, the government is requiring housing association developers to ‘sweat their assets’ and increase their gearing. The Spending Review announcement for 2015-16 confirmed that the main financing model for affordable housing development will remain broadly unchanged up to 2018.

The minimal borrowing needs of the late 1980s and early 90s were easily met by high street banks and building societies, offering 25 or 30 year finance at low rates. As financing needs grew through the 1990s and 2000s, housing associations tended to revert back to these traditional lenders when they needed new funds or to refinance, and continued to enjoy very favourable rates right up until the financial crash of 2008.

Borrowing was generally on a secured basis against specific housing stock assets. Lenders took a first charge against the secured assets and set a series of financial covenants, effectively limiting housing association gearing and requiring levels of interest cover that safeguard the borrower’s ability to pay.

The world of finance changed for housing associations in 2008 as surely as it did for most other businesses looking to borrow from traditional banking sources. HAs had already had some limited exposure to the bond markets, often indirectly through aggregating vehicles. But from 2008, facing higher borrowing requirements to finance large development programmes with more limited government grants, and with the traditional banks and building societies offering only short-term money at higher margins than previously, housing associations’ need to engage with the bond market more consistently became acute.

They have managed this reasonably well so far, as the figures for 2012/13 attest, when associations accounted for roughly 20% of all bond issuance. But the learning curve has been steep for both the HAs and many of the still limited number of institutional investors who have provided debt.

The social business structure of HAs and investor attitudes

The evidence suggests that investors are still coming to terms with the nature of housing association businesses. Despite their phenomenal growth over the past 20 years, housing associations have maintained and, in the light of the Coalition government’s latest radical changes, consciously reaffirmed their status as independent sector social businesses. While their outlook and some of their activity has had to become more commercial, the majority remain charitable, not-for-profit organisations where the ‘social’ is as important as the ‘business’.

Though the core activity of a housing association is building and managing homes for social rent, they deliberately undertake some activity, including social and economic development activity in communities, which generally has no immediate commercial return but supports neighbourhood stability and thus the long-term value of assets. Other non-core activities, such as building homes for market sale or part sale/part rent, are specifically to generate profits. Overall, associations derive about 16% of revenues from non-core activity.

But all housing association profits, whether from rents, asset sales or other commercial activities, are reinvested into their business operations rather than being distributed to directors or shareholders. Value is captured in the business, rather than leaking out in dividends and other payments. Non-executive directors receive minimal remuneration and are often professional people with a range of relevant skills who join HA boards primarily to ‘put something back’ in society. Yet they have significant legal responsibilities within increasingly large scale organisations turning over hundreds of millions of pounds a year. Unsurprisingly, given the nature of the sector and the social consequences should things go wrong, housing association boards have tended to be innately conservative when considering commercial opportunities.

In assessing risk within housing associations, some investors have struggled to understand the potential impacts of non-core activity on the core business and assets. Associations publish relatively limited information on their activities and togther with their lack of long-term exposure to the bond markets, this can make their activities and financial arrangements seem somewhat opaque to investors. At present, the regulatory ring-fence for housing association core assets also looks more permeable than for utilities due to cross-subsidy and financing arrangements.

Although no housing association has ever been allowed to fail and the rating agencies factor in extraordinary government support in the event of financial distress, social housing is not a universally required service. This can make it feel less critical politically and in national infrastructure terms than utility assets and provision. To investor eyes, no government is going to let people’s water be turned off, but just maybe ministers could let a social housing organisation go to the wall.

In reality, while the political, social and economic fallout may not be so black and white as with utilities, there are excellent reasons for the ratings agencies’ assumption that government will come to the rescue of a housing association in extremis. In a country with a huge housing supply shortfall and where an increasing proportion of the population struggles to afford housing costs, the political consequences of allowing thousands of low rent social homes to be sold off at knock down prices by creditors while tenants were potentially made homeless and public money invested in the homes disappeared would be severe indeed.

Still, belief amongst investors that the government and regulator would step in to save the core assets of a housing association does not seem so solidly welded into the investment risk calculation as for the regulated utilities. How legitimate are these concerns? Are housing associations genuinely a more risky investment or would longer, deeper and more regular exposure to housing association business models and the regulatory construct they operate under

assuage investor perceptions? And are water and energy utilities as fail-safe an investment as they appear to be?

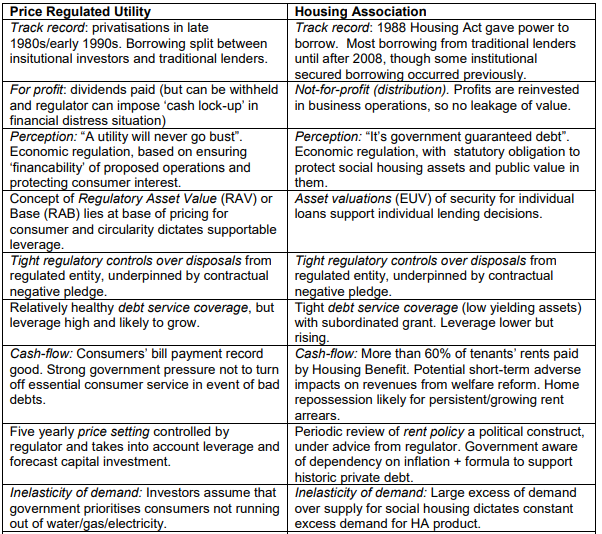

Relative strengths of the utility and housing association constructs

The brief history of the way business and financing models have evolved shows that utility companies and housing associations are undoubtedly very different beasts. Yet, as the introduction to this paper illustrates, there are considerable and important similarities too, and comparison between the relative strengths of the two sectors could be revealing from an investor’s point of view.

Investors have liked the simplicity and certainty inherent in the utility model. Essentially, they provide a vital, reliable universally needed product at a price set regularly with their regulator. Companies’ success in that task is obvious – the lights either work or they don’t; the water comes out of the tap or it doesn’t.

While housing is also universally needed, housing associations focus primarily on providing homes to certain segments of the housing market (about 18% of households in England live in social rented housing). And what constitutes success in terms of the quality and price of product and the sustainability of communities is a more complicated issue.

Given the very different nature of their operations, it is not surprising that utilities and housing associations view their assets, plan ahead, manage risk, manage their financing requirements and work with their respective regulators in different ways. That does not necessarily make one model superior to the other. This section offers a more detailed assessment of the comparative constructs.

The broad regulatory framework

The utility regulators, Ofgem and Ofwat, were established by statute, and the legal framework continues to be set through UK and European legislation. The regulators operate independently of the government executive, but with accountability to parliament.

They were established as economic regulators, setting the pricing mechanism for utilities at five yearly intervals, scrutinising the companies’ costs and investments, monitoring and comparing the services provided by companies, and encouraging competition ‘where this benefits consumers’. Security and sustainability of supply and protecting the consumer interest is a priority. The utility companies are required to publish certain performance information and regulatory compliance statements annually and the regulators have significant powers of enforcement.

The basic legal framework of duties and powers under which the regulators operate has remained stable pretty much since its inception, although the nature of regulation is now beginning to change in both the water and energy industries.

For housing associations, there is also a statutory framework of regulation, but it has been subject to considerable change in recent years. Until 2008, the Housing Corporation acted as the government agency providing development grants and regulating the housing association sector. The Housing Corporation was then disbanded and its functions split between an investment agency (the Homes and Communities Agency (HCA)) and a new regulator, the Tenant Services Authority (TSA), responsible for a new system of co-regulation with the sector.

The Coalition government made further changes through the Localism Act 2011, abolishing the TSA as part of its bonfire of the quangos and reverting to a single investment and regulation body. Regulation passed to a new Regulation Committee of the HCA, though the co-regulation principle was retained. The HCA now regulates all registered social housing providers, including housing associations, local authorities and a small but growing band of private providers.

In some ways, the Regulation Committee is a unique regulatory construct, created to maintain confidence in the housing regulatory framework during a period of major change. While the Committee sits within the HCA, it acts with a high degree of autonomy and at a certain distance from the rest of the HCA. The chief executive of the HCA has overall accountability for regulation, but does not sit on the Committee. However, two members of the Regulation Committee sit on the HCA board.

Unlike the utilities regulators, the HCA is directly supervised by the Communities and Local Government department and some aspects (particularly budgeting) are subject to ministerial control, albeit at arms-length.

As with the utilities, the primary role of the housing association regulator is economic regulation, though with some differences in precisely what is regulated and how. The Regulation Committee is statutorily required to ensure the ongoing viability of HAs, including examining financial and governance arrangements. Value for money is part of the regulatory assessment, providing an efficiency focus similar to the utility regulators’ efficiency targets. Protection of the consumer, which had been beefed up under the TSA, is now limited to setting standards and intervening only where there is risk of ‘serious detriment’ to tenants.

As with the water utilities, regulation is risk-based, with prime responsibility for organisational performance resting with the housing association board and the regulator focusing attention on those organisations most exposed to risk. Housing associations are required to publish certain performance information, and each year the regulator publishes a graded assessment on the viability and governance of all providers with more than 1,000 homes. There are strong powers of regulatory intervention and enforcement.

Price controls

For utilities, the main mechanism for determining consumer prices and the value of the assets is through the five yearly reviews of the Regulatory Asset Base (RAB). The RAB is a financial construct providing a proxy value of the utility’s regulated operating assets, on which the companies are able to earn a return.

While the precise delineation of what sits within the RAB may vary a little between regulated sectors and from price review to price review, the main elements of the RAB are the asset base uprated by inflation for each year of the five year period, an agreed capital expenditure uplift for reinvestment in assets over the five year period including the cost of capital to finance the programme, and an offset to meet agreed capital and operating efficiency targets set by the regulator. There is also an offset to take account of proceeds from any anticipated disposals of assets, and an asset depreciation calculation is factored into the final RAB.

Essentially, at the beginning of each five year period the utility company and the regulator agree what the company’s revenues need to be in order to cover inflation and costs the company will incur to deliver its reinvestment programme and regulatory targets. Consumers are then charged accordingly. The process is transparent and at the end of it the regulator effectively signs off on each company’s five year business plan (though there are moves afoot to reduce the level of business plan prescription in the next price review). Investors have a clear line of sight over the borrowing company’s ability to pay interest on its debts, which offers a high level of certainty.

The regulator sets the price for utilities without interference from government. Impacts on the utilities from government policy, such as climate change obligations, have an evident influence over pricing review decisions, but form only part of the equation.

Price control for housing associations is more obviously a political decision. The rents regime has been very stable for 15 years and, in the 2015-16 Spending Review, announced in June 2013, the government provided certainty for a further 10 year

period. From 2015 housing association rents will be allowed to rise annually by CPI + 1%. This is broadly equivalent to the current regime where housing associations can raise rents by RPI + 0.5% each year (with a further uplift of a maximum £2 a week

where necessary to bring levels into line with the local ‘target rent’).

While there is no direct linkage between rent increases and housing association capital expenditure programmes or cost of debt, there is a direct link to cover inflationary costs, plus some further upward adjustment. Consequently, if a housing association were to stop developing new homes, say because of potential cash flow issues or a risk re-assessment, it becomes cash generative very quickly and most would rapidly regain financial strength.

Unlike the utilities, a large proportion of housing association rental revenues are also effectively provided by the State through the payment of Housing Benefit to welfare dependent tenants. Over 60% of HA tenants require Housing Benefit to help pay their rent. Both utilities and housing associations enjoy a strong bill payment record from their customers, but utilities do not have government-backed revenue streams.

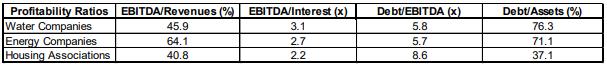

The table below compares a number of key financial ratios between the regulated utilities and housing associations in a broad attempt to gauge relative financial strength.

Immediately apparent is that, while operating margins between the sectors are similar, in debt/EBITDA terms housing association gearing1 is materially higher than for either energy2 or water companies3 , and this is reflected in lower EBITDA interest coverage for HAs. On that basis housing association finances look a little more stretched, although the absolute level of interest cover is still very reasonable.

Moreover, housing associations have a number of levers at their disposal to generate cash, for example through asset sales in a liquid property market on a vacant possession or existing use basis.

When unencumbered assets are factored in, housing associations benefit from the £44 billion of historic grant on their balance sheets received from government to build homes, and even with assets valued for balance sheet purposes at cost less depreciation, leverage is less than 40%. Historic grant would almost certainly act as first loss in the event of any housing association default, mopping up most losses. This should offer considerable comfort to investors.

The true value of housing association assets on an open market basis would also be much higher, particularly given the house price inflation of the last 20 years. So the manner in which association balance sheets are stated arguably disguises a large hidden reserve.

In comparison, most utility company asset bases4 are highly geared, even after RPI indexing, and are comparatively illiquid. This would tend to limit strategic options in the event of financial problems.

Regulators’ enforcement powers

The enforcement powers of the utility regulators and the housing association regulator have many similarities. An element of competition within the energy sector and anti-competitive behaviour regulation mean the position between housing associations and the water utilities is probably most analogous (both sector regulators are looking to increase competition in the future, though the pace is likely to be slow).

Ofwat and the Homes and Communities Agency both operate a gradually escalating enforcement process, pursuing informal regulatory action first wherever possible and moving to formal and proportionate enforcement only where contraventions become serious. The HCA has a statutory duty to minimise interference.

1 HA data is for ‘traditional’ housing associations from ‘Global Accounts of Housing Associations 2012’,

published by the HCA, 2013.

2 Using data from Southern Gas Networks, Scotland Gas Networks and Wales & West (FYE 3/12) as a

proxy

3 Using mean data from 7 water companies as shown in S&P’s report ‘Regulation provides stability for

Uk water companies, but high leverage limits their room for manoeuvre.’ Feb 2012

4 As represented by Regulated Capital Value for water companies ans Regulated Asset Value for

energy companies

Just as Ofwat has key objectives to protect supply to customers and set prices in a way that can support reinvestment in the infrastructure, so the HCA is statutorily required to ensure core social housing assets are not put at risk, to protect the public value in the assets, and help ensure social housing providers can continue to attract necessary finance.

The two sector regulators can both:

- Require additional information and institute investigations

- Issue enforcement orders

- Impose financial penalties

- Ultimately, require and help broker a transfer of core assets to another provider

While Ofwat and Ofgem can impose very substantial financial penalties of up to 10% of a utility’s turnover, and this is a key tool in their enforcement armoury, the HCA has limited financial penalty powers. This makes sense, as serious fines for profit reinvesting housing associations would probably ultimately serve to harm asset delivery. The HCA is more likely to place an association under ‘supervision’ and if necessary act to change an HA’s governance, for example by making statutory appointments of new members to the board to ensure compliance and implement a

change in business or financial strategy.

In the most serious cases, where viability is threatened, utility regulators can order a cash lock-in while a problem is resolved or, ultimately, revoke a company’s licence and administer a transfer of core assets to a viable provider. The regulator’s statutory responsibility is not to any individual company but to protect the regulated core infrastructure and ensure the stability of supply to the customer.

In the equivalent situation in the housing association world, the HCA has a statutory duty to protect core social housing assets and the public value of those assets. If this could not be achieved through a supervision, the HCA would act to broker a voluntary, orderly transfer of assets to another provider or, where this proves impossible within the timeframe available, to impose a 28 day moratorium on the sale of any assets (extendable with the consent of lenders) to provide time to finalise a solution. At the end of the moratorium period, if no solution seemed likely to be found, the HCA could step aside and allow a sale of assets by the provider or its secured creditors. In all likelihood, this would result in mortgage holders making orderly sales of properties to other housing associations.

In exceptional circumstances and with government approval, the HCA can also provide financial assistance itself in the form of a loan, guarantee or indemnity to an association to tide it over while a resolution to a serious viability problem is found.

Intervention record and outcomes

Ofwat has imposed a total of eight financial penalties on five different companies since 2005, but has never been required to revoke a water company’s licence. In 2001 when Enron, the owner of Wessex Water, collapsed, the water company organised the sale of its own ring-fenced assets to YTL, a Malaysian energy group. Ofwat maintained a watching brief over what was a market-managed exercise.

In the somewhat more market-driven energy sector, Ofgem has taken a relatively firm and active stance to enforcement and is now consulting on new standards of conduct for the companies it regulates. Since 2010 Ofgem has completed 14 full scale investigations and levied fines of £35 million. It imposed nine fines on seven companies in 2011/12 alone for non-compliance with standards, and recently launched new investigations into six energy companies for failing to meet government energy efficiency targets. In April 2013, SSE were fined over £10 million

for mis-selling practices.

Utility companies are not immune to failure. For example, in 2002 to prevent a default the UK government pumped £650 million into British Energy, the privatised nuclear power operator supplying 20% of the country’s electricity supply. British Energy blamed the failure on competition from a liberalised energy generation market and clean-up costs it inherited with the infrastructure. But the company clearly had serious management issues. In mid-August 2002 it paid shareholders a large dividend; on 5th September it applied for state aid. Plc status is no guarantee of high quality management in the utilities or any other market sector, as has been shown many times.

Although the HCA does not yet impose requirements on housing associations around ring-fencing (this may change soon), it does have a specific role to prevent organisational failure because of the impact on the ability of the sector as a whole to finance its future investment requirements on reasonable terms, and the potential impact on public funding already supplied and sitting on housing association balance sheets.

Consequently, no housing association has ever been allowed to fail. There have been three occasions in recent years, however, where the regulator has needed to broker a transfer of assets and engagements and/or provide extraordinary financial support. West Hampstead HA was provided with a guaranteed line of credit approved

by the Secretary of State to avoid non-payment and shortly thereafter transferred its assets to another association. Ujima HA and, most recently, Cosmopolitan HA both had rescues co-ordinated by the HCA involving a transfer of assets and liabilities to a single much larger and stronger housing association.

In total, the regulator has resolved around 60 supervisory cases of varying seriousness in recent years from amongst the 1,500 associations. No investor has ever lost money by lending to a housing association and all core social housing assets and non-core assets have been protected.

How rating agencies assess the relative sectors’ strengths

Of 30 issuer ratings for the social housing sector, Moody’s rates 28 housing associations at A1 or A2, one at Aa3 and one at A3. Moody’s ratings of 14 water companies are mostly at A3 or Baa1, with three companies rated at Baa2.

The housing association ratings assume the government will step in with extraordinary support in the event of need, as has always been the case up to now. However, looking solely at Moody’s baseline credit assessment (BCA) of the intrinsic strength of housing association credit and ignoring the possibility of government support, the ratings are still equivalent to those for the water companies. The BCA’s for housing associations are virtually all in the range of A3-Baa2, with one at A2 and one at Baa3 (see appendix).

Essentially, Moody’s rates housing associations in a similar way to public sector entities such as local government and universities, even though HAs are independent of government.

Overall, it regards the level of regulatory oversight and powers as strong and wide ranging and believes the regulator has an effective track record in resolving cases of financial difficulty. However, the Cosmopolitan HA case in 2012-2013 suggested some weaknesses in the regulatory framework in Moody’s view. A one notch downgrade across the sector in May 2013 to the credit levels above reflected the agency’s revised and more cautious assessment of the strength and capacity of the government and regulator to provide extraordinary support. The outlook for the sector

is now classed as Stable.

In April 2013 the HCA published a discussion document aimed at hardening the ringfence substantially and ensuring housing associations develop detailed recovery plans to mitigate any impacts caused by financial distress.

Moody’s rates the water utilities against four key considerations: the regulatory environment and asset ownership model, operational characteristics and asset risk, stability of the business model and financial structure, and key credit metrics. Broadly, this is not dissimilar to rating housing associations according to intrinsic financial strength and the prospects of extraordinary support, albeit Ofwat would coordinate necessary actions in the event of financial distress rather than government through the HCA in the case of housing associations.

Utility companies are explicitly required under their licences to maintain an investment grade rating from credit rating agencies, while Ofwat and Ofgem have a legally enshrined duty of ‘financeability’, ensuring utilities will always have the financial and operational resources to fulfil their obligations. Key within this for rating agency comfort are the regular Regulated Asset Base reviews and the hard ringfence, including the possibility of a cash lock-up requiring regulator consent for all transactions except day to day operations should credit deterioration threaten investment grade status.

Standard & Poor’s believes that, in practice, Ofwat’s ratings target for regulated water utilities is probably higher than the lowest investment grade (S&P: BBB-) and the regulator could seek to take action if ratings fell below their current BBB+ – BBB levels. Utilities financed through corporate securitisations are analysed differently, with generally higher ratings around A- for senior debt and BBB ratings for Class B debt, reflecting structural enhancements not available to conventional corporate entities.

The few HAs rated by S&P have ratings in the range AA to A+, above the ratings of even the securitised utilities. S&P has not downgraded the HA sector in the wake of the Cosmopolitan affair.

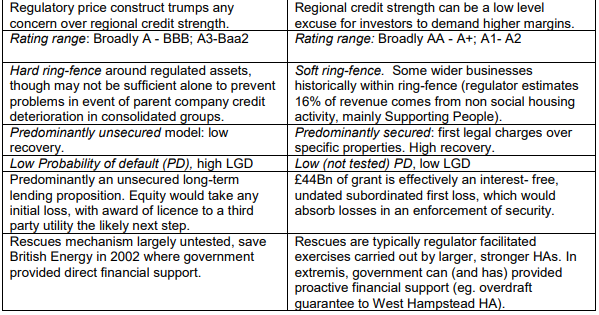

Summary of relative sector strengths and weaknesses

The future investment opportunity

The analysis above indicates that both utilities and housing associations represent very low risk investment. Revenues are predictable, stable and inflation-linked from largely captive markets, neither sector is yet testing the limits of its ability to borrow, and there is strong regulatory oversight with a well established mechanism for managing situations where risk might crystallise, with core assets protected.

The utilities currently have an advantage in terms of the strength of the regulatory ring-fence. They tend to be somewhat more highly leveraged than housing associations, but their debt service coverage tends to be better and helps provide a level of headroom into the future. Housing association leverage is lower but growing and their lower yielding assets mean debt service coverage is tighter, though asset yields should improve with the introduction of Affordable Rents last year.

Overall, however, the credit ratings agencies view housing associations as a somewhat better credit risk, principally because of the assumed benefit of extraordinary government support in the event of need. Even without extraordinary support, they are rated an equivalent risk to utilities.

However, both sectors are facing new challenges for the future which could influence their relative attractiveness for investors.

Utility challenges

Utility regulation is about to undergo some of the biggest changes since its inception. In the energy sector, the regulator is introducing the RIIO model (Revenues = Incentives + Innovation + Outputs). This new price control framework began in April 2013 and aims to secure delivery of £30 billion of new investment to develop sustainable energy and protect security of supply while ensuring fair prices for customers. A more extensive system of financial rewards or penalties relating to service performance will increase the emphasis on companies to deliver the output targets agreed with the regulator. The new price controls will run for eight years instead of five as previously.

At the same time, Ofgem is implementing the government’s policy of reducing the volume and complexity of energy tariffs through its retail market review. The aim is to encourage more consumer switching to cheaper tariffs and greater market competition, with an onus on the companies to make their relative tariff offers much clearer. There is some potential for this to impact on energy company revenues, depending on how it is implemented in practice. New rules will also oblige the companies to treat customers fairly. These measures will start to take effect this August and will be fully in place by March 2014.

The water industry has seen important changes in recent years, including the adoption of private sewers in 2011, which increased wastewater networks considerably, and the introduction of the Service Incentive Mechanism, designed to drive up customer service.

Ofwat’s proposals for the 2015-2020 pricing period will lead to much greater change in the operating environment. There will be separate price limits for the wholesale and retail segments. The wholesale businesses will retain all of the existing regulated capital value and prices will continue to be inflation-linked. But there will be no automatic indexing of retail prices for customers. While the new wholesale proposals aim to encourage more innovative and sustainable use of water resources, the retail business proposals aim to increase competition for business customers and greater efficiency for individual household customers.

Ofwat is also introducing an ‘outcomes’ approach, where performance against regulatory delivery targets is likely to be more closely scrutinised, with a system of financial rewards and penalties depending on performance and possible trade-offs between performance results against different targets. The intention is to push the water companies much harder to focus on customers’ service priorities, with more freedom and incentive to innovate to keep costs down. The Customer Challenge Groups Ofwat has required the companies to set up will help establish the business plan targets to be met.

The ratings agencies believe the utilities will face a considerably tougher operating environment over the next price period, with major infrastructure investment requirements, more taxing efficiency and customer service obligations and increasing competition, which could impact on business risk profiles and the ratings stance if profit margins reduce or cash flow becomes more volatile.

Housing association challenges

Housing associations, meanwhile, face their own challenges. Most notably, the government’s welfare benefit reforms, such as direct payment of Housing Benefit to tenants, the ‘bedroom’ tax and the total benefits cap, are likely to have some impact on revenues (the cap mostly affecting tenants in the South). Universal Credit and the uprating of benefits by less than RPI may further impact on tenants’ ability to pay.

Housing associations are also starting to engage more consistently in commercial activities, as they seek to develop additional cash sources to compensate for much lower government grant rates on new development. Building for market sale, market renting programmes and selling of services are all relatively new activities for housing associations and bring a greater level of market exposure and risk. Development competition is growing, too, with the Homes and Communities Agency registering a small but rising number of private companies and local authorities as affordable housing providers and eligible for grant funding.

The 2013 Spending Review decisions removed one further source of uncertainty, at least for the short-term, with the government providing new capital subsidies for affordable home building between 2015 and 2018 at roughly equivalent levels to the 2011-15 programme. In a very constrained overall government spending envelope, this was a decent settlement for the housing sector, helped by the government’s desire to boost growth through infrastructure investments. What happens after this will probably depend on how successful the government’s efforts to reduce debt have been in the interim.

As independent bodies, however, housing associations have the option of not taking part in development if they consider the government’s terms too onerous. While most of the large housing associations would not take such a decision lightly (for both social and business reasons), they are not under any compulsion to build new homes.

Moody’s views any structural loss of income for housing associations from weak rent collection once welfare reform is fully implemented as highly unlikely and believes the impacts are manageable. It notes, too, that associations have been resilient to weaker conditions in the housing market in terms of both volumes and prices, and can reduce capital expenditure programmes in response to government policy and market conditions, where necessary.

Broadly speaking, for both utilities and housing associations, while there are changes afoot with clear adverse potential, the challenges look manageable and both sectors remain a very strong and low risk investment opportunity into the future, as things stand. Uncertainties may lead to changes in spreads, but seem unlikely to prevent either sector accessing funds.

Can housing associations raise their investment market share?

Overall, the discrepancy between market investment in utilities and housing associations looks too great, given that the sectors have considerable similarities in terms of safety of investment, near-monopoly supply positions, and strong and stable revenue streams offering long-term steady returns. The potential for housing associations to increase their bond market share looks good, therefore, and there are a number of actions the sector could take to help make it happen.

Some of the difference in investment perception and current scale is almost certainly due to history. The utilities have a long track record of engagement with the institutional investment market, whereas the large majority of housing association bond issues have taken place in the past three years. Investors have had 20 years experience of assessing and analysing the utility sector and are comfortable they know the benefits and downsides an investment in a utility might represent.

Most of the utility companies have well established bond curves and there is a good level of clarity for investors over the likely medium-term pipeline of issuance. Individual housing association issuers have come to the market a maximum of 2-3 times so far, though The Housing Finance Corporation, the main HA sector aggregating vehicle, has issued 44 bonds on behalf of clients since 1988. The forward financing needs of housing associations are also less obvious to the market.

Utilities operate a business model and structure investors can readily recognise and understand from their dealings with other private sector businesses. The housing association model and structure is less well known, far less common in the investment market, and, in some ways, more complex to understand.

Greater and longer exposure to the sector and more analysis of its undoubted strengths will help to overcome some of these uncertainties. Housing associations looking for investment have a clear job to do in engaging more concertedly and regularly with potential investors so levels of understanding and comfort can grow more quickly.

Publication of more meaningful information on a regular basis by housing associations around financial and service performance could also support investor awareness and confidence. With individual investment analysts often covering 4-5 different sectors, it is inevitable they will focus more on some than others and each sector will have a limited opportunity to get its message across, whether in face-time or on paper.

Analysts who are short of time are more likely to concentrate on sectors they know, feel confident about and where they see a clear pipeline of opportunity. New issuers to the market have to demonstrate that it is worth the analyst’s time to understand their business, particularly in a context where banks have cut their lending and the competition for bond finance is intense.

When the water regulator wanted to encourage more inflation-linked bond issuance to the utilities in the mid-2000s, it undertook a campaign of engagement with investors to assess the appetite and raise awareness of the opportunity. Similarly, the Homes and Communities Agency could support more housing association bond issues by increased engagement with investors. It is understood the HCA is considering running investor roadshows, based upon the annual publication of HA sector Global Accounts1. Given the competition for bond finance, the HCA should include international investors, who are starting to enter the market in greater numbers and remain a largely untapped source for UK housing associations.

One clear divide between the utilty and housing association sectors is in the nature of the regulatory ring-fence. While the housing association regulator’s track record in dealing with the small number of very serious viability issues within the sector should provide good comfort, non-core activity is rising and the sector probably needs to go further to demonstrate that risks are properly managed and investment risk remains low.

The regulator has recognised this. In April 2013 the HCA’s Regulation Committee published a consultation document, ‘Protecting social housing assets in a more diverse sector’. It details proposals to amend the regulatory framework to institute explicit requirements ensuring protection for regulated assets, more in line with the hard ring-fence operated by utilities. These include housing associations undertaking social housing activity within a discrete corporate entity restricted almost exclusively to carrying out regulated business and associations being required to draw up a recovery plan that can be swiftly implemented in the event of a serious financial problem. These additional requirements would complement the already extensive enforcement and intervention powers available to the HCA.

There is some way to go before these proposals assume a final shape. The nature of housing association businesses makes it very difficult to regulate cost of capital in the same way as happens within the utility sector. There are concerns from housing associations that too constrictive a ring-fence could impact on their ability to manage their businesses effectively to increase housing supply and invest in communities. However, some form of additional regulatory requirement to protect social housing assets will almost certainly be implemented in 2014.

While the regulator works on putting these changes in place, investors could (and often have) put their money in far riskier sectors than safe and solid housing associations. It is a sector well worth another, deeper look.

Appendix

Credit agency rating of housing association and utility companies

Related Articles

News

AHF Retained Bond Sale

The Government guaranteed aggregator Affordable Housing Finance (AHF) priced a retained bond sale transaction today for Cornerstone Housing, the 1,300.

2016-01-22

News

AHF Starts New Year of Bond Issuance

Only 12 days into the New Year, Affordable Housing Finance (AHF), the Government Guaranteed funding aggregator has brought its 12th.

2017-01-12